Sometimes we find ourselves in the philosophical corner, and this time the inspiration fairy knocked on our door after a meeting with Greenpeace where the proposals for Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) were a topic.

We are very positive to protecting the marine areas in general, and feel it is time to address the issue more openly.

Why is there a need for Marine Protected Areas?

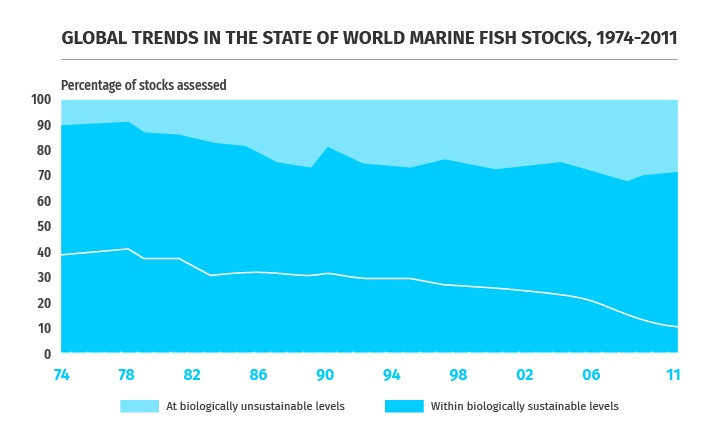

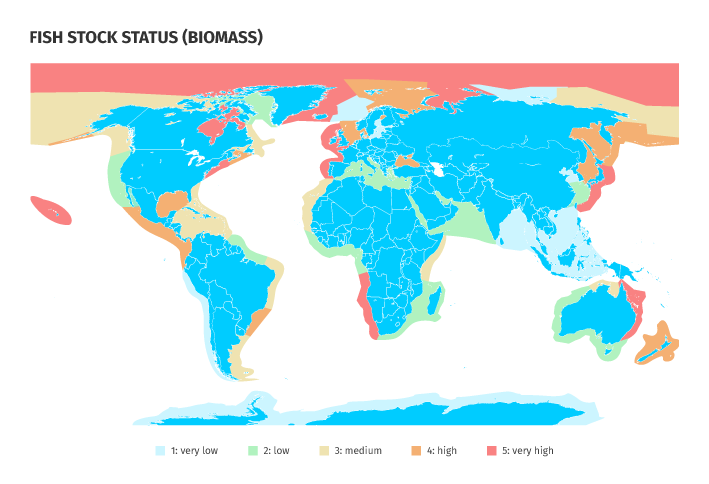

MPA’s are not only about fisheries but they seem to be a big part of the rationale behind it. What we know today is that poorly regulated fishing activities and humankind’s inclination to exploit natural resources have caused a situation where 85% of the world’s fish stocks are either overfished or fished to capacity.

Source: FAO 2016

Marine protected areas are a vital complement to sustainable fisheries management, helping maintain the diverse web of ocean life and bolstering resilience of ocean systems in the face of threats including climate change. They protect fragile nursery habitats and vulnerable species and help support the entire marine ecosystem.

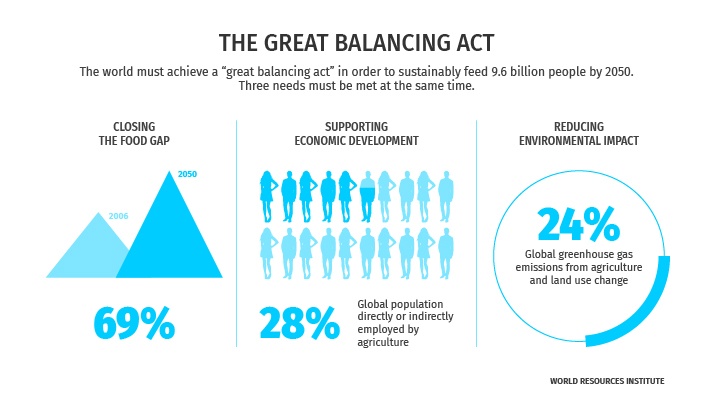

Furthermore, we know that unless we find a clever non-cannibalistic way of controlling the population growth (or Elon Musk succeeds with creating our second home on Mars), we are likely to be 9.7 billion people on earth in 2050 who need to be fed in a less CO2-intensive way.

Source: World Resources Institute

Source: World Resources Institute

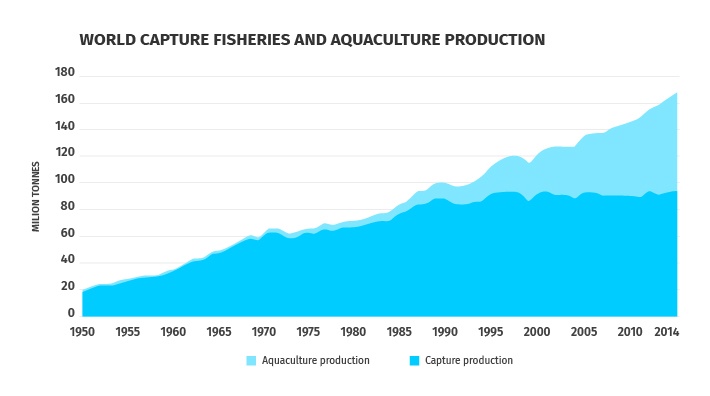

Have I lost you? I hope not, because I am getting back to MPAs in a minute. I promise. Because, you see, in order to produce enough sustainable seafood for the population we have to grow our aquaculture, which depends on marine ingredients from wild caught fisheries. This is not only important for the health of the farmed fish, but also for it to keep the natural balance of omega-3s when consumed by humans.

Source: FAO 2016

There is a need for Marine Protected Areas to protect biodiversity, since we over the last 40 years have lost almost 50% of the world’s species to extinction, but also in order to rebuild fish stocks that have been overfished to be able to meet future food demand without destroying our planet.

The following map shows catch as percentage of total biomass.

Source: Sea Around Us (University of British Columbia)

How will we succeed with the establishment of Marine Protected Areas?

There is a global ambition to establish marine protected areas that together make up 30% of our oceans. This is actually a sub target of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) number 14 that we have committed ourselves to be part of solving.

There is no single roadmap for us to guide us how to go about making an MPA, but I have to say that The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has done some great work on the different ideas of what an MPA may look like. They have ended up with six different categories, which you can find here. It is a short and sweet overview.

To me it seems clear that one must look to apply the full scale of different MPA categories to reach the 30 % goal and allow for sustainable fisheries to coexist alongside MPAs. We believe that it is not beneficial to close all these areas into no fish zones, if, and only if, the fisheries operating within those zones are precautionary and not threatened by overfishing. Although we see the need to have no-take zones to increase climate resilience and build species protection of important critical feeding habitats.

The protected area categories are under review these days to fit with changing conservation needs, and the MPAs referred to in Greenpeace’s report are not formally adopted by the regulatory body (CCAMLR) governing the conservation of marine living resources like the Antarctic krill. We have always aimed to do the right thing, and are in dialogue with scientists and the environmental NGOs to explore possibilities for voluntary zones with our industry peers.

We are positive towards the creation of MPAs to create good reference areas for science, but you must remember that there is no “one size fits all” for marine protection. Nor is it enough to draw lines on a map because marine resources ‘swim’ and can move between the areas we as humans decide to protect. Nevertheless, it should be backed up by scientific work.

We believe that sustainable fisheries and marine protected areas can and should coexist.

So we do not want to bore you with the facts, but if you are not yet familiar with what it means to operate a sustainable fishery, here are four key points to what it entails.

1. A sustainable fishery means that it is harvested below the species’ ability to regenerate itself and for its biomass to live on.

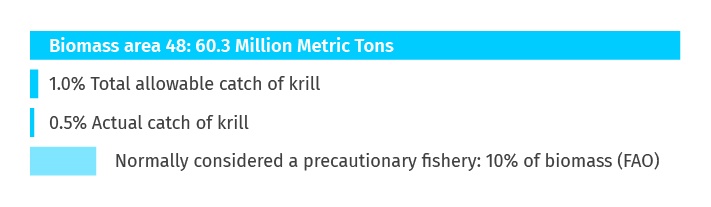

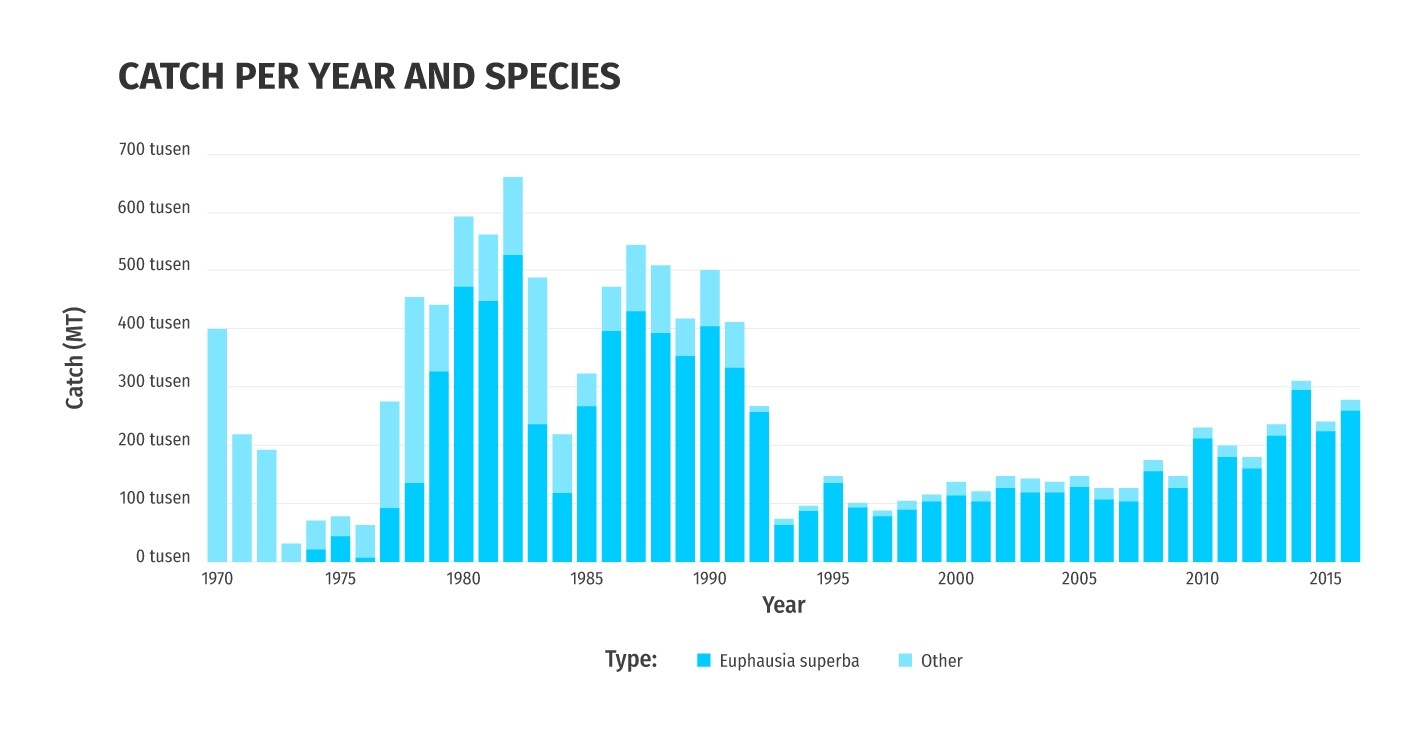

For a normal fishery that means having a catch below 10% of the biomass (FAO 2016). For the krill fishery, the quota is set to 620.000 Metric tons, which is approximately 1% of the total estimated biomass of the krill.

Source: CCAMLR

But you might have heard that the biomass estimate of Antarctic krill is outdated. But don’t you worry, a new biomass survey is scheduled for Jan/Feb 2019. And for the past 7 years there have been annual krill monitoring surveys that show neither a trend toward increase nor decrease in the overall krill biomass in the Antarctic.

It is important to note that as has done in the small scale surveys, the krill industry will be contributing their fleets, led by independent researches onboard, to make this survey happen. Why? Because they recognize they have an environmental responsibility in these areas and their long-term operations depend on it.

If you need more data and science then you can read a report by Sustainable Fisheries Partnership who for the third year in a row gives the krill fishery in the Antarctic an “A” rating, meaning the operations is in “very good condition”.

2. A sustainable fishery is one where all catches of the species are well reported and transparent.

With the requirements set by CCAMLR to operate a krill fishery in the Antarctic region, plus the specific requirement to have an independent observer on board each krill harvesting vessel to ensure proper reporting of species catch volumes, it is practically impossible to illegally fish for krill. Although all the data is reported, there is still potential for improvement in making this readily available. We are working on putting up a site where we will publish data on our harvesting activities and transshipment.

Source: CCAMLR

If you are interested to learn more about the precautionary management of Antarctic Krill, I would recommend this research paper.

3. A sustainable fishery has low levels of by-catch.

Making sure that the fishery has almost no by-catch is part of being sustainable. Along with being fully transparent.

The krill fisheries have been evaluated in a full assessment against Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) standards, and the independent expert team found the fisheries to be in full compliance with the MSC standards. Annual surveillance takes place in the MSC program on these fisheries, and this surveillance process continues to confirm high performance. As Camiel Derichs, Regional Director Europe at Marine Stewardship Council openly admits, few other fisheries in the MSC program score as high in their assessments as Aker BioMarine’s Antarctic krill fisheries.

4. A sustainable fishery has an ecosystem-based management that takes into account the entire ecosystem and not the harvested biomass alone.

The regulatory body for marine life in Antarctica is CCAMLR, which is extremely stable and requires the consensus of 25 nations and the EU in order to make any changes. The quota for krill is set based on historical catch and precautionary catch limits, taking into consideration the well-being of all the other species in the Antarctic ecosystem. Actually, the krill fishery is far more conservative than the quotas of normal fisheries because of all the animals that depend on krill as a food source, as well as the unique environment in which they live.

Source: Aker BioMarine annual report

If you haven't read our annual report, I would like to share a thought from Prof. Stephen Nicols: “A lot of individuals and groups would prefer that the Antarctic krill industry ceased to exist. If you take away the fishery, you take away the CAMLR-convention, meaning that Antarctic marine life would no longer be protected by a comprehensive convention. Having a limited, sustainably managed krill fishery is a small price to pay for such a comprehensive environmental agreement.”

Useful links:

- Sustainability - our foundation

- MSC re-certification report

- SFP report

- Research paper on precautionary management of krill